Cricket is omnipresent in India, but the films that reference the sport have mostly been banal, the ads star-obsessed, and fiction bordering on nil

Ashok Malik

March 7, 2011

| |||

| | |||

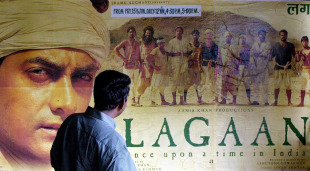

In 2001, the Hindi film Lagaan opened to rapturous reviews and sizzling ticket sales. A year later, it made it to an Oscar nomination. The story of an unlikely cricket team of Indian peasants - a rainbow XI with representation across caste and religious lines - Lagaan used a cricket match as the location of anti-colonial protest. The Indians defeated an English team and saved themselves from an oppressive land tax.

Could Lagaan have been made without reference to cricket? The film was clearly anachronistic and ahistorical. In the early 20th century, the period in which it was set, cricket was decidedly an upper-crust pastime in India. It was played by westernised Parsis, Indian princes - who occasionally hired middle-class English and Indian professionals - and the like. Peasants did not so much as touch the bat. If sport had a role in the early stirrings of Indian nationalism, it was in the form of football - a case in point is Mohun Bagan's victory against an English army team in the IFA Shield final in 1911 - and hockey or contact sports such as wrestling.

A nuanced, slow-paced game such as cricket - as opposed to the pulsating, non-stop action of soccer or boxing - is also less likely to make for on-screen drama. Escape to Victory showed a bunch of desperate and determined PoWs playing the Nazis in a football match; you could hardly substitute it with a cricket or chess encounter. On its part, the 1911 IFA Shield final was immortalised recently in a Bengali film called Egaro (The Eleven) that did not, however, climb the heights of Lagaan.

The fact that the makers of Lagaan had to choose cricket was a bow to market forces. Simply put, contemporary India is a one-sport society and the chances of a cricket-centric film succeeding are exponentially higher than that of a football or hockey film. This truism explains several things. It points to why the overwhelming majority of sports-based films in India have featured cricket - Saheb had a footballer hero, Mein Inteqam Loonga and Apne had Dharmendra turning pugilist, but these are oddball exceptions - but also suggests that insofar as sport is present in India's popular culture, it is likely to talk the language of cricket. Indeed, even the father of the British-Indian schoolgirl footballer in Bend It Like Beckham was a frustrated cricketer.

Not that the cricket films have been particularly memorable or meaningful. Lagaan was spectacularly produced and, in parts, gripping. Iqbal (2005), the tale of a special-needs child with phenomenal bowling talent, and to a lesser extent Jannat (2008), about corruption in the game, made a mark. Stumped (2003) was original in that in mocked India's cricket obsession. It showed an army wife, worried that her husband has gone missing during the Kargil War, while the rest of the neighbourhood couldn't be bothered and is focused only on the 1999 World Cup, which overlaps with the India-Pakistan military conflict. Made in Tamil, Chennai 600028 was a no-star film on rivalries between two street cricket teams.

Aside from these, cricket films have been banal. Awwal Number featured Dev Anand as former cricketer, chief selector and also inspector-general of police. If it was bizarre, films starring real-life cricketers, such as Kabhi Ajnabi The (Sandeep Patil)) and Cricketer (Kapil Dev; Marc Zuber played his on-screen team-mate) sank without a trace. With the Indian diaspora increasingly a market for Hindi film makers, Patiala House - loosely based on the life of Monty Panesar, the first Sikh to play for England - was waiting for happen. A biopic of Lalit Modi has also been announced, though it is unclear whether his character will be the wronged hero or the villain. It can be argued that cinema and cricket have an uneasy relationship in India because as social phenomena they are just so similar. The very format of cricket's youngest child - the Indian Premier League - is designed to provide a three-hour match that will be a counter-attraction to a three-hour film, complete with action, superstars, music and a dance routine thrown in. In public adulation, hero worship and as advertisement models and props, cricketers are matched only by movie stars.

| India is recognised as the new home of cricket. What then is the Indian civilisational stamp on cricket? Does it appreciate that love of cricket and love of India (or of the Indian cricket team) are neither coterminous nor mutually exclusive? Where are the museums to cricket in an economy that contributes 70% of the game's revenues? | |||

There is a small difference though. Cricketers have shorter career spans, even if, at their peak, they are bigger endorsers and evoke greater mass hysteria than film icons. For movie stars, length more than makes up for depth: They are in the public eye that much longer. Sanjay Manjrekar and Aamir Khan were both born in 1965. Manjrekar made it to the Indian team in November 1987; a few months later, Khan released his first film. Today, Manjrekar has long retired; Aamir Khan is still playing a college student. At 40, a movie star has life in him; a cricketer is contemplating a behind-the-scenes existence.

Aside from its testy relationship with the film industry, does cricket trigger art at all? Wall murals are a signature of football fandom in Latin America. In India, cities such as Kolkata have adopted this for cricketers. Music, especially custom-created songs, provides another aspect. In 2007, India's World Cup campaign began to the rhythms of "Mind and body, heart and soul …", a pulsating number composed by Shankar, Ehsan and Loy. The Indian team got hammered in the tournament but the song, commissioned by a credit card provider for a cricket-themed ad campaign, lingered in the public imagination. By the end, it was devoid of its original cricket association.

The evolution of cricket-related advertising is telling. In the early days - Farookh Engineer appearing in a Brylcream ad or Sunil Gavaskar dressed in a Dinesh suit length - a single cricketer shared space with a brand that was perhaps equally well-known. Today's cricketer ads can be multi-starrers - Sachin Tendulkar and Harbhajan Singh out for a safari in Africa; MS Dhoni and random players setting off for a quick break from a rain-interrupted match - and the story and narrative of the ad can be so long and convoluted that they may actually inhibit product recall. You are more likely to remember the cricketer, even watch the cricketer, than watch the ad.

Nevertheless, the use of cricketers in advertisements has kept pace with the history of Indian cricket. The Amul ads - a one-line pun on a contemporary issue, updated week after week, month after month - have often invoked cricket. As such, in 2010-11, we've had Amul selling its butter with "Sachindcredible appetite" and "V.V.S. Thanxman". Twenty years ago it was: "It's Hadlee surprising that the best reaches the top". In the mid-1990s came "Lara, kya mara". Most memorable perhaps was the rendition of the last-ball six in the Australasia Cup final of 1986: "Miyaan ki daad se Sharma gaye". There's a PhD thesis waiting to be written on the Amul-cricket nexus.

Cricket as pop culture is all very well but what about cricket as high culture - or at least mid-brow culture? The closest one comes to it is Chennai's Cricket Kutcheri, which takes place every winter and features tennis-ball cricket matches between teams of classical musicians. Kutcheri is Tamil for "concert" and this offbeat cricket tournament coincides with Carnatic concerts during Chennai's celebrated season of music, Margazhi (December).

These small examples notwithstanding, is there a big picture? Serious interrogators of cricket see it not as a sport, not even as a culture but as a civilisation. The prototypical construct of the game - the stiff upper lip, the gentle hand-clapping, the obeisance paid to a high priest in a strange white coat and an arcane set of rules nobody quite understands - was in many ways a metaphor for Englishness, for Empire and for playing by the rules, even if you thought those who had drafted them were dictatorial or at least daft. That construct is no longer valid. Cricket has been transformed, as has its society (or societies). India is recognised as the new home of cricket. What then is the Indian civilisational stamp on cricket? Frankly, this is where the story gets disquieting. India celebrates cricket but does it cherish it? Does it appreciate that love of cricket and love of India (or of the Indian cricket team) are neither coterminous nor mutually exclusive? Where are the museums to cricket in an economy that contributes 70% of the game's revenues?

| |||

Cricket commentary on television - and more so, radio - is woefully inadequate. The Indians who appear on television tend to speak better, with grammar and flow, than in the earlier years of live telecast. Yet, so often they seem to duck the challenges of their calling. A combination of how cricket telecast is run in India - the cricket board hires the commentators and camerapersons, and then sells the audio-visual feed to a television network - and the diffidence that shackles any second-rung stakeholder in a monopolistic trade practice means Indian commentators pull their punches.

This system will not allow us to produce our own Fred Trueman or Richie Benaud. In the current "captive commentary team" era, an outspoken but entertaining maverick would be out of place. In another time, Lala Amarnath spoke for everyman in the commentary box; now it's every man for himself. The incestuous and cosy relationship between commentators, crickets, sports agents and cricket authorities makes disinterested, occasionally cutting interventions that much rarer. That essential ingredient of a popular cultural phenomenon - the ability to laugh at oneself - has completely bypassed Indian cricket. Cricket literature in India has a longer tradition, though whether this would qualify as popular culture in the literal sense of the term - that is, engaging to a vast section of the people - is another matter. Some years ago, The Zoya Factor, a novel about a young woman from the ad industry who finds herself in the midst of a cricket situation and exchanging meaningful barbs with the Indian captain, founds readers and married chick lit to crick lit. It didn't spawn a trend though.

Understandably the best cricket writing in India has been in the strictly non-fiction genre. Having said that, despite the books, essays and clutch of felicitous full-time cricket correspondents, the archetypal Indian cricket buff is more likely to be heard screaming "We want sixer" than curling up with Swanton. What has killed the literary market, really, is the mania with getting former cricketers to write columns, each more banal than the next, and filling up sports pages with insipid content.

Is it then an inexorable race to the bottom? Are Indian cricket's pop cultural products (mostly) designed to be anything but tasteful? How about a taut murder mystery that unfolds during a single IPL game ("The cheerleader did it"?) or a compelling television series or film about the tussle for turf between a strong-willed cricket captain and an equally egotistical coach? Some day all of that may happen. For the moment, paint you face, grab that cola and enjoy the World Cup. It's not an ideal cricket culture, but it's the only one we have.

Source: http://www.espncricinfo.com

No comments:

Post a Comment